exp(j-omega-t)

An engineering perspective on life, sport, and fun.

Saturday, April 13, 2019

Thursday, April 21, 2016

Saturday, February 09, 2013

Sat. Morning During Winter

Welcome to Saturday morning during winter when racing is based on a Phoenix schedule...

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Installing a Shimano Hollowtech 2 Crank

Shimano Hollowtech 2 cranksets have 3 distinct parts (not counting complete disassembly which we won't cover here):

1) The drive side crank arm, which includes the crank arm, the spider, the chainrings, and the crank's axle:

2) The non-drive side crank arm

3) The non-drive side crank arm cap

This nice Ultegra crank is purely for illustration of the 3 major parts

Next, push the axle though the drive side of the bottom bracket:

Push, push push. Sometimes (often even) the crank will go easily until about this point, where there's just a little bit of axle showing.

When the drive side is completely in, there shouldn't be and axle showing between the bottom bracket and the inside of the chainring spider:

The axle will now be sticking out the non-drive side of the bottom bracket. Add some grease to both the inside and outside. I like grease any time there is metal on metal contact, it makes the bike a lot less squeaky and helps prevent premature wear.

Slide on the non-drive side crank arm. You'll notice a little tab that is popped up in between the pinch bolts. This little tab wraps around the edge of the axle to ensure that the arm is on fully.

When the arm is on, push the tab down. Don't force it, if it doesn't go down easily, then the non-drive side arm isn't on. This means either that the axle isn't pushed all the way through the bottom bracket, of the non-drive side arm just isn't fully seated. Check both.

Next, prepare the non-drive side arm cap. There's a cool little tool that I have, you'll need some version of the same thing. Grease the threads lightly.

Tighten the cap FINGER TIGHT ONLY! This cap only helps to make sure the crank arm has compression when tightening the pinch screws, it's not load bearing and is only plastic.

Next, tighten the two pinch screws. Alternate sides as you go to ensure that the force is evenly distributed. I believe that his crank 12-15 Nm.

1) The drive side crank arm, which includes the crank arm, the spider, the chainrings, and the crank's axle:

2) The non-drive side crank arm

3) The non-drive side crank arm cap

This nice Ultegra crank is purely for illustration of the 3 major parts

There are any number of nuances to selecting the appropriate bottom bracket, crankset, frame combination. I won't go into any of those here, these instructions assume that you have a frame with an appropriately sized bottom bracket to fit a Shimano crank. If you can't guarantee that, do more homework or ask.

First, apply grease to the axle of the crank where is will rest against the bottom bracket bearings. By grease, I don't mean Vaseline, find a good quality bicycle grease (I've been using Finishline Teflon grease for just about everything and haven't had any problems yet, but the world is filled with people who are extraordinarily picky about the type of grease they use...):

Next, push the axle though the drive side of the bottom bracket:

When that happens, there's no replacement for a rubber mallet and a little whack:

When the drive side is completely in, there shouldn't be and axle showing between the bottom bracket and the inside of the chainring spider:

The axle will now be sticking out the non-drive side of the bottom bracket. Add some grease to both the inside and outside. I like grease any time there is metal on metal contact, it makes the bike a lot less squeaky and helps prevent premature wear.

Slide on the non-drive side crank arm. You'll notice a little tab that is popped up in between the pinch bolts. This little tab wraps around the edge of the axle to ensure that the arm is on fully.

When the arm is on, push the tab down. Don't force it, if it doesn't go down easily, then the non-drive side arm isn't on. This means either that the axle isn't pushed all the way through the bottom bracket, of the non-drive side arm just isn't fully seated. Check both.

Next, prepare the non-drive side arm cap. There's a cool little tool that I have, you'll need some version of the same thing. Grease the threads lightly.

Tighten the cap FINGER TIGHT ONLY! This cap only helps to make sure the crank arm has compression when tightening the pinch screws, it's not load bearing and is only plastic.

Next, tighten the two pinch screws. Alternate sides as you go to ensure that the force is evenly distributed. I believe that his crank 12-15 Nm.

To remove, reverse this process. Popping up the little tab between the pinch bolts is a pain and you might need the mallet to pop the crank out just like you might need it to pop it in.

If the crank you're putting in has different numbers of teeth on the chainrings than the crank you're removing, it's necessary to adjust the length of the chain in order to get proper shifting performance in the whole gear range. If you don't change it, you'll suffer in both the high-high and low-low areas of shifting.

More on that tomorrow...

Chain Stretch

In the interest of bike maintenance...

Let's take a look at how to check the chain stretch.

Bicycle links are based on a 1" link length. This is handy because it gives a nice easy metric for measuring the amount of stretch that a chain has using a simple measuring tape or ruler (I prefer the former for reasons to be explained).

It is possible to buy tools (really nice pretty expensive tools or way cheaper versions of the same thing) that will measure your chain for you, it's easy enough to do on your own.

The technique I learned is to measure a length of chain that is 12 links long, which depending on your gearing can is probably in big ring up front.

I generally measure from the back end of 1 link to the back end of a link 12 links away:

In this case, I only have two hands, so the tape measure is taped in place, but in practice all one has to do is find the length and look, no tape needed. Because each link is 1" long ideally, it would be nice to see the 12th link align with the 12" mark on the ruler (as shown). In reality, wear in the chain will, over time, cause that length to grow. I go by the following guidelines; If the length of 12 links is...

Let's take a look at how to check the chain stretch.

Bicycle links are based on a 1" link length. This is handy because it gives a nice easy metric for measuring the amount of stretch that a chain has using a simple measuring tape or ruler (I prefer the former for reasons to be explained).

It is possible to buy tools (really nice pretty expensive tools or way cheaper versions of the same thing) that will measure your chain for you, it's easy enough to do on your own.

The technique I learned is to measure a length of chain that is 12 links long, which depending on your gearing can is probably in big ring up front.

I generally measure from the back end of 1 link to the back end of a link 12 links away:

In this case, I only have two hands, so the tape measure is taped in place, but in practice all one has to do is find the length and look, no tape needed. Because each link is 1" long ideally, it would be nice to see the 12th link align with the 12" mark on the ruler (as shown). In reality, wear in the chain will, over time, cause that length to grow. I go by the following guidelines; If the length of 12 links is...

- < 1/16" past the 12" mark, go about your business. Your chain is fine.

- > 1/16" but < 1/8", replace your chain.

- > 1/8", you need a new chain and it's worth looking at your crank and cassette teeth to see if you've drastically worn the tooth spacing.

Pretty simple. Chains aren't cheap, but they're cheaper than replacing your crank sprocket or cassette and your chain, so they're completely worth replacing when it's time.

So, what causes stretch?

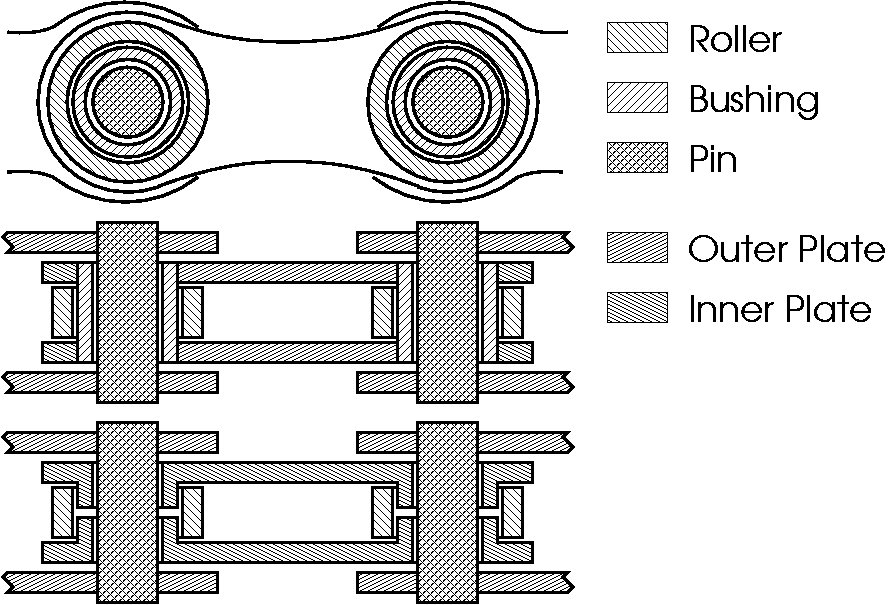

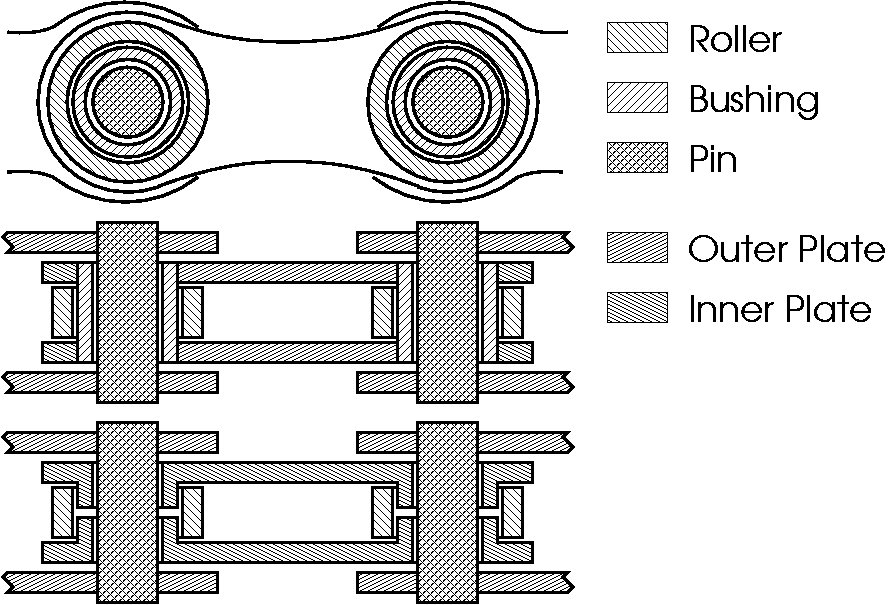

Modern bicycle chains are constructed with inner plates, outer plates and (possibly) roller/bushings with a connecting pin between the two that allow the system to pivot:

Over time, tension on the chain chain under load (pedaling) causes the inner plates and outer plates to dig into the pin as force is transferred between each consecutive link. Eventually, this force gouges the each pin a little and over the space of an entire chain length there is a measurable length increase: chain stretch.

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Moving Beyond Triathlon

Since moving to Arizona, I've changed my athletic focus a bit. I've become a bit frustrated with running due to persistent knee problems (hooray for a life of competitive swimming for making my feet, knees, and hips weak) which have prevented me from running more than 6 miles at a time. So, I decided to take a break from swimming and running (and needless to say triathlon in general) and focus on cycling.

Needless to say, this decision was made right around the first snowfall of the year, which combined with my San Diego weather cycling attire meant a mad dash to find warmer cycling clothes and a lot (a lot!) of indoor trainer rides. While this sounds horrible, this has forced me into several new skills, equipment evaluations, and life related realizations which will be expanded upon in the future.

Since I'm new to cycling, I'm forced to start at the bottom of the pecking order and navigate my way through Cat(agory) 5. It seems simple, 10 mass-start raced with no benefit to finishing place and/or time. The key here being "mass start" which basically boils down to time trials don't count. Bummer, but I guess I can deal with it. Theoretically, I've been told that I can petition Arizona Cycling to be upgraded before 10 races, but I've gotten mixed feedback about whether this actually works or not, so for now the plan is to complete all 10 races. A few comments about my races so far:

1. Crits

My first experience with crit racing was hearing horror stories from friends: Marc striking his pedal (twice) and claiming "never again," and Chris dislocating his finger in a wreck that he couldn't avoid. Not promising. All I can say is that they really are the most frightening cycling experience I've ever had and there really was nothing that could possibly prepare me for someone hitting my handlebars with their elbow in the middle of a fast corner from the inside and then bouncing off the person on my outside, or maybe it was the guy on HED Jet 90s who decided that a 30 mph sweeper in a pack was a great time to take a drink of water... Either way, it's scary because your well-being is subject to the stupidity of the people around you and there is ofter little you can do to control them.

I'm not fond of crits, but to be fair I've only done 3. I think the realization I've had, already, is that I'm not brave enough, or fearless enough, to stick myself positions that I need to be in to do well. I'm not willing to shove my front wheel next to someone in a tight corner to assert my position because the cost of either of us screwing up is too great. Thus, I've not been successful, always trying to use my cardio strength to wear people out over the whole race, rather than sitting in the right position to take advantage of drafts and positioning at the finish.

2. Road Races

This is where I think I excel (or where I hope to excel in the future anyway). Road races are a fun combination of strength, stamina, and tactics that allow for a lot more room and time to adapt to the actions (dare I say stupidity) of the other riders around. I've had great success making sure that I'm in the front, but not taking the wind all the time, and identifying the riders with whom I can ride fast and safe.

On the other hand, I've also realized that I've got a lot to learn. This boils down to the same rookie mistake that I keep making (albeit knowingly) during the large, fast, group rides I do: I always jump too early. I have too much confidence that I can use my stamina to stay away and I'll go for a break from a group too early or with too much warning. This nipped me in the butt on one of the stage races I recently did that finished on a 5 km steep uphill; I felt great and dug in with about 3 km to go only to blow up 1.5 km later only to limp to the finish in 5th. If I had been smart, and just waited another kilometer before I jumped, I'd be the proud winner of the race... but lesson learned.

3. Stage Races

So far these have been the most fun I've had. I think it's because these races have been a combination of a few different events, so I get the chance to rock a TT and have fun in a road race before having to suffer through a crit. I'm hopeful that I'll get the chance to do one in the future that's just road race stages and just eliminate the crit entirely, but I realize the feasibility of this is low because the economics of putting on a crit stage are far, far, better than anything else.

The biggest downside I've found to these races is that they take a lot of time. And not just the racing time each day, but the fact that you have to travel for a few days, and in between stages there's not exactly a ton to do since I've generally been reluctant to go off and do a lot of crazy hiking or walking or exercising in between so as to save my energy for the next day. In a general, it's a lot of fun though, and I think these are the best combination of everything if you can justify spending the time.

That's it for now, more later possibly involving a wheel hub rebuild and/or a fun picture of me falling during my first attempt to ride rollers.

Needless to say, this decision was made right around the first snowfall of the year, which combined with my San Diego weather cycling attire meant a mad dash to find warmer cycling clothes and a lot (a lot!) of indoor trainer rides. While this sounds horrible, this has forced me into several new skills, equipment evaluations, and life related realizations which will be expanded upon in the future.

Since I'm new to cycling, I'm forced to start at the bottom of the pecking order and navigate my way through Cat(agory) 5. It seems simple, 10 mass-start raced with no benefit to finishing place and/or time. The key here being "mass start" which basically boils down to time trials don't count. Bummer, but I guess I can deal with it. Theoretically, I've been told that I can petition Arizona Cycling to be upgraded before 10 races, but I've gotten mixed feedback about whether this actually works or not, so for now the plan is to complete all 10 races. A few comments about my races so far:

1. Crits

My first experience with crit racing was hearing horror stories from friends: Marc striking his pedal (twice) and claiming "never again," and Chris dislocating his finger in a wreck that he couldn't avoid. Not promising. All I can say is that they really are the most frightening cycling experience I've ever had and there really was nothing that could possibly prepare me for someone hitting my handlebars with their elbow in the middle of a fast corner from the inside and then bouncing off the person on my outside, or maybe it was the guy on HED Jet 90s who decided that a 30 mph sweeper in a pack was a great time to take a drink of water... Either way, it's scary because your well-being is subject to the stupidity of the people around you and there is ofter little you can do to control them.

I'm not fond of crits, but to be fair I've only done 3. I think the realization I've had, already, is that I'm not brave enough, or fearless enough, to stick myself positions that I need to be in to do well. I'm not willing to shove my front wheel next to someone in a tight corner to assert my position because the cost of either of us screwing up is too great. Thus, I've not been successful, always trying to use my cardio strength to wear people out over the whole race, rather than sitting in the right position to take advantage of drafts and positioning at the finish.

2. Road Races

This is where I think I excel (or where I hope to excel in the future anyway). Road races are a fun combination of strength, stamina, and tactics that allow for a lot more room and time to adapt to the actions (dare I say stupidity) of the other riders around. I've had great success making sure that I'm in the front, but not taking the wind all the time, and identifying the riders with whom I can ride fast and safe.

On the other hand, I've also realized that I've got a lot to learn. This boils down to the same rookie mistake that I keep making (albeit knowingly) during the large, fast, group rides I do: I always jump too early. I have too much confidence that I can use my stamina to stay away and I'll go for a break from a group too early or with too much warning. This nipped me in the butt on one of the stage races I recently did that finished on a 5 km steep uphill; I felt great and dug in with about 3 km to go only to blow up 1.5 km later only to limp to the finish in 5th. If I had been smart, and just waited another kilometer before I jumped, I'd be the proud winner of the race... but lesson learned.

3. Stage Races

So far these have been the most fun I've had. I think it's because these races have been a combination of a few different events, so I get the chance to rock a TT and have fun in a road race before having to suffer through a crit. I'm hopeful that I'll get the chance to do one in the future that's just road race stages and just eliminate the crit entirely, but I realize the feasibility of this is low because the economics of putting on a crit stage are far, far, better than anything else.

The biggest downside I've found to these races is that they take a lot of time. And not just the racing time each day, but the fact that you have to travel for a few days, and in between stages there's not exactly a ton to do since I've generally been reluctant to go off and do a lot of crazy hiking or walking or exercising in between so as to save my energy for the next day. In a general, it's a lot of fun though, and I think these are the best combination of everything if you can justify spending the time.

That's it for now, more later possibly involving a wheel hub rebuild and/or a fun picture of me falling during my first attempt to ride rollers.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)